Moving From the Old to the New: Research on Reading Comprehension Instruction

Master Body

3. Word Recognition Skills: 1 of Two Essential Components of Reading Comprehension

Maria Due south. Murray

Abstract

After acknowledging the contributions of contempo scientific discoveries in reading that have led to new understandings of reading processes and reading instruction, this chapter focuses on give-and-take recognition, one of the 2 essential components in the Simple View of Reading. The next affiliate focuses on the other essential component, language comprehension. The Unproblematic View of Reading is a model, or a representation, of how skillful reading comprehension develops. Although the Report of the National Reading Console (NRP; National Institute of Child Health and Homo Development [NICHD], 2000) concluded that the best reading instruction incorporates explicit teaching in five areas (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension), its purpose was to review hundreds of enquiry studies to let instructors know the most effective bear witness-based methods for educational activity each. These five areas are featured in the Simple View of Reading in such a way that we can meet how the subskills ultimately contribute to two essential components for skillful reading comprehension. Children require many skills and elements to gain word recognition (e.g., phoneme awareness, phonics), and many skills and elements to gain language comprehension (e.g., vocabulary). Ultimately, the ability to read words (word recognition) and sympathize those words (linguistic communication comprehension) lead to proficient reading comprehension. Both this chapter and the next chapter nowadays the skills, elements, and components of reading using the framework of the Simple View of Reading, and in this particular chapter, the focus is on elements that contribute to automatic word recognition. An explanation of each chemical element'south importance is provided, along with recommendations of research-based instructional activities for each.

Learning Objectives

Later reading this chapter, readers will be able to

- place the underlying elements of discussion recognition;

- identify enquiry-based instructional activities to teach phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition of irregular sight words;

- discuss how the underlying elements of word recognition lead to successful reading comprehension.

Introduction

Throughout history, many seemingly logical beliefs have been debunked through enquiry and science. Alchemists once believed lead could be turned into gold. Physicians once assumed the flushed red skin that occurred during a fever was due to an abundance of blood, and so the "cure" was to remove the excess using leeches (Worsley, 2011). People believed that the earth was flat, that the sunday orbited the globe, and until the discovery of microorganisms such every bit bacteria and viruses, they believed that epidemics and plagues were caused past bad air (Byrne, 2012). One past one, these misconceptions were dispelled as a upshot of scientific discovery. The same can be said for misconceptions in teaching, peculiarly in how children learn to read and how they should be taught to read.1

In just the terminal few decades there has been a massive shift in what is known almost the processes of learning to read. Hundreds of scientific studies take provided us with valuable cognition regarding what occurs in our brains as we read. For example, we now know there are specific areas in the brain that process the sounds in our spoken words, dispelling prior beliefs that reading is a visual activeness requiring memorization (Rayner, Foorman, Perfetti, Pesetsky, & Seidenberg, 2001). Also, nosotros now know how the reading processes of students who learn to read with ease differ from those who observe learning to read difficult. For case, nosotros accept learned that irregular center movements do not cause reading difficulty. Many clever experiments (see Rayner et al., 2001) have shown that skilled readers' eye movements during reading are smoother than struggling readers' because they are able to read with such ease that they do not take to continually stop to figure out letters and words. Perhaps most valuable to future teachers is the fact that a multitude of studies accept converged, showing us which instruction is almost constructive in helping people learn to read. For instance, we now know that phonics instruction that is systematic (i.east., phonics elements are taught in an organized sequence that progresses from the simplest patterns to those that are more complex) and explicit (i.e., the teacher explicitly points out what is being taught every bit opposed to allowing students to figure it out on their ain) is virtually effective for educational activity students to read words (NRP, 2000).

Every bit you volition acquire, word recognition, or the ability to read words accurately and automatically, is a complex, multifaceted process that teachers must understand in order to provide effective instruction. Fortunately, nosotros now know a great deal about how to teach word recognition due to of import discoveries from current research. In this affiliate, you will learn what research has shown to be the necessary elements for didactics the underlying skills and elements that atomic number 82 to accurate and automatic word recognition, which is one of the two essential components that leads to skilful reading comprehension. In this textbook, reading comprehension is defined as "the process of simultaneously extracting and amalgam meaning through interaction and interest with written language" (Snowfall, 2002, p. xiii), besides as the "capacities, abilities, knowledge, and experiences" one brings to the reading situation (p. 11).

Learning to Read Words Is a Circuitous Process

It used to be a widely held belief by prominent literacy theorists, such equally Goodman (1967), that learning to read, like learning to talk, is a natural process. Information technology was thought that since children learn language and how to speak but past virtue of being spoken to, reading to and with children should naturally lead to learning to read, or recognize, words. At present we know it is non natural, even though information technology seems that some children "pick upwards reading" like a bird learns to fly. The human brain is wired from birth for speech, but this is not the case for reading the printed discussion. This is because what nosotros read—our alphabetic script—is an invention, only available to humankind for the last three,800 years (Dehaene, 2009). Equally a result, our brains have had to arrange a new pathway to interpret the squiggles that are our letters into the sounds of our spoken words that they symbolize. This seemingly simple task is, in actuality, a complex feat.

The alphabet is an amazing invention that allows united states of america to correspond both old and new words and ideas with just a few symbols. Despite its efficiency and simplicity, the alphabet is actually the root cause of reading difficulties for many people. The letters that make upwards our alphabet represent phonemes—individual spoken communication sounds—or according to Dehaene, "atoms" of spoken words (as opposed to other scripts like Chinese whereby the characters stand for larger units of speech communication such as syllables or whole words). Individual speech sounds in spoken words (phonemes) are difficult to notice for approximately 25% to forty% of children (Adams, Foorman, Lundberg, & Beeler, 1998). In fact, for some children, the ability to observe, or become aware of the individual sounds in spoken words (phoneme awareness) proves to be one of the most hard academic tasks they volition ever run into. If nosotros were to inquire, "How many sounds do you hear when I say 'gum'?" some children may answer that they hear simply one, because when we say the word "mucilage," the sounds of /g/ /u/ and /m/ are seamless. (Note the / / marks announce the sound made by a letter.) This ways that the sounds are coarticulated; they overlap and melt into each other, forming an enveloped, single unit of measurement—the spoken word "gum." In that location are no well-baked boundaries between the sounds when we say the word "gum." The /g/ sound folds into the /u/ sound, which then folds into the /thousand/ audio, with no breaks in between.

So why the difficulty and where does much of it brainstorm? Our speech consists of whole words, but we write those words by breaking them down into their phonemes and representing each phoneme with letters. To read and write using our alphabetic script, children must first be able to detect and disconnect each of the sounds in spoken words. They must blend the individual sounds together to make a whole word (read). And they must segment the individual sounds to stand for each with alphabetic letters (spell and write). This is the kickoff stumbling cake for so many in their literacy journeys—a difficulty in phoneme sensation only considering their brains happen to be wired in such a style as to brand the sounds difficult to find. Research, through the use of encephalon imaging and various clever experiments, has shown how the encephalon must "teach itself" to accommodate this alphabet by creating a pathway between multiple areas (Dehaene, 2009).

Instruction incorporating phoneme awareness is likely to facilitate successful reading (Adams et al., 1998; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998), and it is for this reason that it is a focus in early on school experiences. For some children, phoneme awareness, along with exposure to additional fundamentals, such every bit how to hold a book, the concept of a word or sentence, or knowledge of the alphabet, may exist learned earlier formal schooling begins. In addition to having such print experiences, oral experiences such as being talked to and read to within a literacy rich surroundings help to gear up the stage for reading. Children defective these literacy experiences prior to starting school must rely heavily on their teachers to provide them.

The Unproblematic View of Reading and the Strands of Early Literacy Development

Teachers of reading share the goal of helping students develop skillful reading comprehension. Equally mentioned previously, the Unproblematic View of Reading (Gough & Tunmer, 1986) is a research-supported representation of how reading comprehension develops. It characterizes skillful reading comprehension as a combination of 2 carve up but equally of import components—word recognition skills and linguistic communication comprehension power. In other words, to unlock comprehension of text, two keys are required—being able to read the words on the page and understanding what the words and linguistic communication mean inside the texts children are reading (Davis, 2006). If a pupil cannot recognize words on the folio accurately and automatically, fluency will be afflicted, and in plow, reading comprehension will endure. Likewise, if a student has poor understanding of the meaning of the words, reading comprehension will suffer. Students who have success with reading comprehension are those who are skilled in both word recognition and language comprehension.

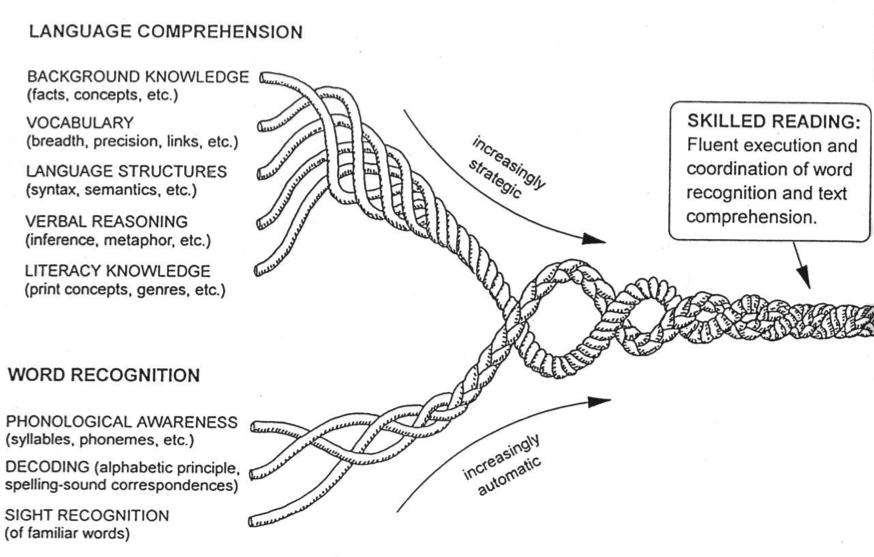

These two essential components of the Unproblematic View of Reading are represented past an illustration past Scarborough (2002). In her illustration, seen in Figure 1, twisting ropes correspond the underlying skills and elements that come together to course two necessary braids that represent the two essential components of reading comprehension. Although the model itself is called "simple" because it points out that reading comprehension is comprised of reading words and understanding the language of the words, in truth the two components are quite complex. Examination of Scarborough's rope model reveals how multifaceted each is. For either of the two essential components to develop successfully, students demand to be taught the elements necessary for automated word recognition (i.due east., phonological awareness, decoding, sight recognition of frequent/familiar words), and strategic linguistic communication comprehension (i.e., background knowledge, vocabulary, verbal reasoning, literacy cognition). The sections below volition draw the importance of the three elements that lead to authentic discussion recognition and provide evidence-based instructional methods for each element. Affiliate four in this textbook volition encompass the elements leading to strategic language comprehension.

Word Recognition

Word recognition is the deed of seeing a word and recognizing its pronunciation immediately and without any witting effort. If reading words requires conscious, effortful decoding, little attending is left for comprehension of a text to occur. Since reading comprehension is the ultimate goal in teaching children to read, a disquisitional early objective is to ensure that they are able to read words with instant, automatic recognition (Garnett, 2011). What does automated word recognition look like? Consider your own reading as an example. Assuming you are a skilled reader, it is likely that as you are looking at the words on this page, you cannot avoid reading them. It is impossible to suppress reading the words that you wait at on a page. Considering you take learned to instantly recognize and so many words to the point of automaticity, a mere glance with no conscious effort is all it takes for word recognition to have place. Despite this word recognition that results from a mere glance at impress, it is critical to empathize that you have not simply recognized what the words wait like as wholes, or familiar shapes. Even though we read then many words automatically and instantaneously, our brains notwithstanding process every letter in the words subconsciously. This is evident when nosotros spot misspellings. For example, when rapidly glancing at the words in the familiar sentences, "Jack be nimble, Jack be quick. Jack jamped over the canbleslick," you probable spotted a trouble with a few of the individual messages. Yes, you instantly recognized the words, notwithstanding at the same time you noticed the private messages inside the words that are not correct.

To teach students word recognition so that they tin reach this automaticity, students require instruction in: phonological sensation, decoding, and sight recognition of high frequency words (eastward.1000., "said," "put"). Each of these elements is defined and their importance is described below, along with effective methods of instruction for each.

Phonological Awareness

One of the critical requirements for decoding, and ultimately word recognition, is phonological awareness (Snow et al., 1998). Phonological sensation is a broad term encompassing an sensation of various-sized units of sounds in spoken words such as rhymes (whole words), syllables (large parts of words), and phonemes (individual sounds). Hearing "cat" and "mat," and being aware that they rhyme, is a form of phonological sensation, and rhyming is usually the easiest and earliest class that children larn. Likewise, existence able to break the spoken word "teacher" into 2 syllables is a grade of phonological awareness that is more than sophisticated. Phoneme awareness, as mentioned previously, is an sensation of the smallest individual units of sound in a spoken word—its phonemes; phoneme awareness is the most advanced level of phonological sensation. Upon hearing the word "sleigh," children will exist enlightened that there are iii carve up speech sounds—/s/ /l/ /ā/—despite the fact that they may take no idea what the word looks like in its printed form and despite the fact that they would likely have difficulty reading information technology.

Because the terms audio similar, phonological awareness is often confused with phoneme awareness. Teachers should know the difference because sensation of larger units of sound—such as rhymes and syllables—develops before awareness of individual phonemes, and instructional activities meant to develop i awareness may not be suitable for some other. Teachers should as well empathise and remember that neither phonological awareness nor its most advanced form—phoneme awareness—has anything whatever to exercise with print or letters. The activities that are used to teach them are entirely auditory. To assist remember this, simply picture that they can be performed by students if their eyes are closed. Adults can teach phonological sensation activities to a child in a auto seat during a drive. The child tin be told, "Say 'cowboy.' Now say 'cowboy' without saying 'moo-cow.'" Adults tin can teach phoneme awareness activities as well by asking, "What sound do you hear at the commencement of 'sssun,' 'sssail,' and 'ssssoup'?" or, "In the give-and-take 'snack,' how many sounds do you lot hear?" or by proverb, "Tell me the sounds y'all hear in 'lap.'" Notice that the words would not be printed anywhere; only spoken words are required. Engaging in these game-like tasks with spoken words helps children develop the sensation of phonemes, which, along with additional education, will facilitate futurity word recognition.

Why phonological awareness is important

An abundance of research emerged in the 1970s documenting the importance of phoneme awareness (the most sophisticated class of phonological awareness) for learning to read and write (International Reading Association, 1998). Failing to develop this sensation of the sounds in spoken words leads to difficulties learning the relationship between speech and print that is necessary for learning to read (Snow et al., 1998). This difficulty can sometimes be linked to specific underlying causes, such equally a lack of instructional experiences to help children develop phoneme awareness, or neurobiological differences that make developing an sensation of phonemes more hard for some children (Rayner et al., 2001). Phoneme awareness facilitates the essential connexion that is "reading": the sequences of individual sounds in spoken words lucifer upward to sequences of printed letters on a folio. To illustrate the connection between phoneme sensation and reading, picture the steps that children must perform as they are get-go to read and spell words. First, they must accurately sound out the messages, one at a fourth dimension, holding them in retention, and and so blend them together correctly to course a give-and-take. Conversely, when starting time to spell words, they must segment a spoken word (even if information technology is not aural they are even so "hearing the word" in their minds) into its phonemes and then represent each phoneme with its respective letter(s). Therefore, both reading and spelling are dependent on the power to segment and alloy phonemes, every bit well equally lucifer the sounds to letters, and as stated previously, some students have great difficulty developing these skills. The good news is that these important skills can exist effectively taught, which leads to a discussion about the most effective ways to teach phonological (and phoneme) sensation.

Phonological awareness education

The National Reading Panel (NRP, 2000) report synthesized 52 experimental studies that featured instructional activities involving both phonological awareness (e.g., categorizing words similar in either initial sound or rhyme) and phoneme awareness (e.g., segmenting or blending phonemes). In this section, both volition be discussed.

A scientifically based study by Bradley and Bryant (1983) featured an action that teaches phonological awareness and remains pop today. The action is sorting or categorizing pictures by either rhyme or initial sound (Bradley & Bryant, 1983). Equally shown in Effigy 2, sets of cards are shown to children that feature pictures of words that rhyme or have the same initial sound. Typically one flick does not lucifer the others in the group, and the students must decide which the "odd" 1 is. For instance, pictures of a fan, can, man, and pig are identified to be sure the students know what they are. The teacher slowly pronounces each give-and-take to brand sure the students clearly hear the sounds and has them point to the word that does non rhyme (match the others). This is ofttimes referred to as an "oddity task," and it can also be washed with pictures featuring the same initial sound as in key, clock, cat, and scissors (see Blachman, Brawl, Black, & Tangel, 2000 for reproducible examples).

Evidence-based activities to promote phoneme awareness typically have students segment spoken words into phonemes or take them blend phonemes together to create words. In fact, the NRP (2000) identified segmenting and blending activities as the virtually effective when educational activity phoneme awareness. This makes sense, considering that segmenting and blending are the very acts performed when spelling (segmenting a discussion into its private sounds) and reading (blending letter of the alphabet sounds together to create a word). The NRP noted that if segmenting and blending activities eventually incorporate the use of letters, thereby allowing students to make the connection between sounds in spoken words and their corresponding letters, there is even greater benefit to reading and spelling. Making connections between sounds and their corresponding messages is the beginning of phonics instruction, which will exist described in more detail below.

An activity that incorporates both segmenting and blending was first developed by a Russian psychologist named Elkonin (1963), and thus, it is ofttimes referred to as "Elkonin Boxes." Children are shown a moving picture representing a 3- or four-phoneme film (such as "fan" or "lamp") and told to move a bit for each phoneme into a serial of boxes below the picture. For case, if the word is "fan," they would say /fffff/ while moving a fleck into the first box, then say /aaaaa/ while moving a chip into the 2nd box, and so on. Both Elkonin boxes (see Figure three) and a similar activity called "Say Information technology and Move It" are used in the published phonological awareness preparation manual, Road to the Lawmaking by Blachman et al. (2000). In each activity children must listen to a give-and-take and movement a corresponding fleck to indicate the segmented sounds they hear, and they must likewise blend the sounds together to say the entire word.

Decoding

Another critical component for discussion recognition is the ability to decode words. When teaching children to accurately decode words, they must understand the alphabetic principle and know letter-sound correspondences. When students make the connexion that letters signify the sounds that we say, they are said to understand the purpose of the alphabetic code, or the "alphabetic principle." Letter-sound correspondences are known when students can provide the right sound for letters and letter combinations. Students tin can then exist taught to decode, which means to blend the letter sounds together to read words. Decoding is a deliberate human action in which readers must "consciously and deliberately apply their knowledge of the mapping arrangement to produce a plausible pronunciation of a word they do not instantly recognize" (Brook & Juel, 1995, p. 9). One time a word is accurately decoded a few times, it is probable to get recognized without conscious deliberation, leading to efficient word recognition.

The instructional practices teachers use to teach students how letters (e.g., i, r, x) and letter clusters (due east.one thousand., sh, oa, igh) correspond to the sounds of speech in English is called phonics (not to be dislocated with phoneme awareness). For example, a teacher may provide a phonics lesson on how "p" and "h" combine to make /f/ in "phane," and "graph." Later all, the alphabet is a code that symbolizes speech sounds, and once students are taught which sound(southward) each of the symbols (letters) represents, they can successfully decode written words, or "crack the code."

Why decoding is important

Similar to phonological awareness, neither understanding the alphabetic principle nor knowledge of letter of the alphabet-audio correspondences come naturally. Some children are able to proceeds insights about the connections between spoken communication and impress on their ain just from exposure and rich literacy experiences, while many others require educational activity. Such instruction results in dramatic improvement in give-and-take recognition (Boyer & Ehri, 2011). Students who understand the alphabetic principle and have been taught letter-sound correspondences, through the use of phonological awareness and alphabetic character-sound didactics, are well-prepared to begin decoding simple words such as "true cat" and "big" accurately and independently. These students will have high initial accuracy in decoding, which in itself is important since it increases the likelihood that children volition willingly appoint in reading, and as a result, word recognition will progress. Also, providing students effective instruction in letter of the alphabet-sound correspondences and how to apply those correspondences to decode is important because the resulting benefits to word recognition lead to benefits in reading comprehension (Brady, 2011).

Decoding instruction

Pedagogy children letter of the alphabet-sound correspondences and how to decode may seem remarkably simple and straightforward. Yet education them well plenty and early enough then that children tin can begin to read and comprehend books independently is influenced past the kind of instruction that is provided. There are many programs and methods available for teaching students to decode, but extensive evidence exists that instruction that is both systematic and explicit is more than effective than instruction that is not (Brady, 2011; NRP, 2000).

As mentioned previously, systematic instruction features a logical sequence of letters and letter combinations starting time with those that are the almost common and useful, and ending with those that are less and then. For example, knowing the letter "s" is more than useful in reading and spelling than knowing "j" considering information technology appears in more words. Explicit pedagogy is direct; the teacher is straightforward in pointing out the connections between letters and sounds and how to use them to decode words and does not exit information technology to the students to effigy out the connections on their ain from texts. The notable findings of the NRP (2000) regarding systematic and explicit phonics instruction include that its influence on reading is most substantial when it is introduced in kindergarten and commencement class, it is constructive in both preventing and remediating reading difficulties, it is effective in improving both the ability to decode words besides as reading comprehension in younger children, and it is helpful to children from all socioeconomic levels. Information technology is worth noting here that effective phonics instruction in the early on grades is important then that difficulties with decoding exercise not persist for students in later grades. When this happens, it is often noticeable when students in heart school or loftier school struggle to decode unfamiliar, multisyllabic words.

When providing instruction in letter-audio correspondences, we should avert presenting them in alphabetical order. Instead, it is more than effective to brainstorm with loftier utility letters such as "a, yard, t, i, s, d, r, f, o, thousand, l" then that students can begin to decode dozens of words featuring these common messages (e.g., mat, fit, rag, lot). Another reason to avoid teaching letter of the alphabet-audio correspondences in alphabetical lodge is to prevent letter-sound confusion. Letter confusion occurs in similarly shaped messages (e.g., b/d, p/q, g/p) because in day-to-solar day life, irresolute the direction or orientation of an object such as a purse or a vacuum does non change its identity—information technology remains a purse or a vacuum. Some children do non sympathise that for certain letters, their position in space can alter their identity. Information technology may accept a while for children to empathize that changing the direction of letter b will brand it into letter d, and that these symbols are not only called unlike things but too have different sounds. Until students proceeds experience with print—both reading and writing—confusions are typical and are non due to "seeing letters astern." Nor are confusions a "sign" of dyslexia, which is a type of reading problem that causes difficulty with reading and spelling words (International Dyslexia Association, 2015). Students with dyslexia may reverse letters more often when they read or spell considering they accept fewer experiences with print—not because they see letters backward. To reduce the likelihood of confusion, teach the /d/ sound for "d" to the bespeak that the students know it consistently, earlier introducing letter "b."

To introduce the alphabetic principle, the Elkonin Boxes or "Say It and Move It" activities described above tin be adapted to include messages on some of the fries. For example, the alphabetic character "north" can exist printed on a chip and when students are directed to segment the words "nut," "man," or "snap," they tin can motion the "n" flake to represent which sound (eastward.g., the commencement, second, or last) is /n/. Equally letter of the alphabet-sound correspondences are taught, children should brainstorm to decode by blending them together to form real words (Blachman & Tangel, 2008).

For many students, blending letter sounds together is difficult. Some may feel letter-by-letter of the alphabet distortion when sounding out words i letter at a time. For example, they may read "mat" as muh-a-tuh , adding the "uh" audio to the end of consonant sounds. To preclude this, letter sounds should be taught in such a way to make sure the student does not add the "uh" sound (eastward.one thousand., "one thousand" should be learned equally /mmmm/ not /muh/, "r" should be learned as /rrrr/ not /ruh/). To teach students how to blend letter sounds together to read words, information technology is helpful to model (run across Blachman & Murray, 2012). Brainstorm with two letter words such as "at." Write the two messages of the give-and-take separated by a long line: a_______t. Indicate to the "a" and demonstrate stretching out the short /a/ sound—/aaaa/ as you move your finger to the "t" to smoothly connect the /a/ to the /t/. Repeat this a few times, decreasing the length of the line/time between the ii sounds until you lot pronounce it together: /at/. Gradually move on to three letter words such equally "sad" past instruction how to blend the initial consonant with the vowel sound (/sa/) then adding the final consonant. It is helpful at first to use continuous sounds in the initial position (due east.g., /s/, /k/, /50/) because they can be stretched and held longer than a "terminate consonant" (e.thou., /b/, /t/, /one thousand/).

An fantabulous activity featured in many scientifically-based research studies that teaches students to decode a word thoroughly and accurately past paying attention to all of the sounds in words rather than guessing based on the initial sounds is word building using a pocket chart with letter cards (see examples in Blachman & Tangel). Have students begin by building a discussion such equally "pan" using letter cards p, a, and northward. (These can be made using index cards cut into iv 3″ x 1.25″ sections. Information technology is helpful to draw attending to the vowels past making them red as they are often difficult to remember and hands confused). Adjacent, have them modify just one sound in "pan" to make a new word: "pat." The sequence of words may proceed with just one letter changing at a time: pan — pat — rat — sabbatum — sit — sip — tip — tap — rap. The student will brainstorm to sympathise that they must listen advisedly to which sound has changed (which helps their phoneme sensation) and that all sounds in a word are important. Every bit new phonics elements are taught, the letter sequences change accordingly. For example, a sequence featuring consonant blends and silent-e may wait similar this: slim—slime—slide—glide—glade—blade—blame—shame—sham. Many decoding programs that feature strategies based on scientifically-based research include discussion building and provide samples ranging from easy, beginning sequences to those that are more than advanced (Beck & Beck, 2013; Blachman & Tangel, 2008).

A final of import point to mention with regard to decoding is that teachers must consider what makes words (or texts) decodable in order to let for adequate practice of new decoding skills. When letters in a word conform to common alphabetic character-sound correspondences, the word is decodable because it can be sounded out, every bit opposed to words containing "rule breaker" letters and sounds that are in words like "colonel" and "of." The letter-sound correspondences and phonics elements that have been learned must be considered. For example, even though the letters in the word "shake" conform to common pronunciations, if a pupil has non nonetheless learned the audio that "sh" makes, or the phonics rule for a long vowel when there is a silent "e," this particular word is non decodable for that child. Teachers should refrain from giving children texts featuring "ship" or "shut" to exercise decoding skills until they take been taught the audio of /sh/. Children who take merely been taught the sounds of /s/ and /h/ may decode "shut" /due south/ /h/ /u/ /t/, which would not lead to high initial accuracy and may atomic number 82 to confusion.

Sight Word Recognition

The third critical component for successful word recognition is sight discussion recognition. A pocket-size percentage of words cannot exist identified by deliberately sounding them out, yet they appear frequently in print. They are "exceptions" because some of their letters practise not follow common letter-sound correspondences. Examples of such words are "once," "put," and "does." (Detect that in the give-and-take "put," still, that merely the vowel makes an exception sound, different the sound it would make in similar words such as "gut," "rut," or "but.") Equally a result of the irregularities, exception words must exist memorized; sounding them out will not work.

Since these exception words must often be memorized equally a visual unit of measurement (i.eastward., by sight), they are frequently chosen "sight words," and this leads to defoliation amid teachers. This is considering words that occur ofttimes in print, even those that are decodable (e.1000., "in," "volition," and "can"), are too often called "sight words." Of course it is important for these decodable, highly frequent words to be learned early (preferably by attending to their sounds rather than just past memorization), correct along with the others that are not decodable because they announced so ofttimes in the texts that will be read. For the purposes of this chapter, sight words are familiar, loftier frequency words that must be memorized considering they take irregular spellings and cannot be perfectly decoded.

Why sight discussion recognition is important

I third of beginning readers' texts are by and large comprised of familiar, high frequency words such as "the" and "of," and well-nigh half of the words in impress are comprised of the 100 almost mutual words (Fry, Kress, & Fountoukidis, 2000). It is no wonder that these words demand to be learned to the point of automaticity so that smooth, fluent give-and-take recognition and reading can take identify.

Interestingly, skilled readers who decode well tend to get skilled sight word "recognizers," meaning that they learn irregular sight words more than readily than those who decode with difficulty (Gough & Walsh, 1991). This reason is because as they begin learning to read, they are taught to exist aware of phonemes, they learn alphabetic character-sound correspondences, and they put it all together to brainstorm decoding while practicing reading books. While reading a lot of books, they are repeatedly exposed to irregularly spelled, highly frequent sight words, and as a result of this repetition, they learn sight words to automaticity. Therefore, irregularly spelled sight words tin can be learned from wide, independent reading of books. Notwithstanding, children who struggle learning to decode do not spend a lot of fourth dimension practicing reading books, and therefore, practice not encounter irregularly spelled sight words as oftentimes. These students will need more deliberate didactics and additional practice opportunities.

Sight word recognition didactics

Teachers should notice that the majority of letters in many irregularly spelled words exercise in fact follow regular sound-symbol pronunciations (east.g., in the give-and-take "from" only the "o" is irregular), and as a result attending to the messages and sounds tin often lead to right pronunciation. That is why it is however helpful to teach students to notice all letters in words to anchor them in memory, rather than to encourage "guess reading" or "looking at the first letter," which are both highly unreliable strategies equally anyone who has worked with young readers will attest. Interestingly, Tunmer and Chapman (2002) discovered that beginning readers who read unknown words by "sounding them out" outperformed children who employed strategies such as guessing, looking at the pictures, rereading the sentence on measures of word reading and reading comprehension, at the end of their beginning twelvemonth in schoolhouse and at the eye of their third twelvemonth in school.

Other than developing sight word recognition from wide, independent reading of books or from exposure on classroom word walls, education in learning sight words is similar to instruction used to learn letter-audio correspondences. Sources of irregularly spelled sight words can vary. For instance, they can exist preselected from the text that will be used for that day's reading instruction. Lists of irregularly spelled sight words tin be found in reading programs or on the Internet (search for Fry lists or Dolch lists). When using such lists, determine which words are irregularly spelled considering they will also feature highly frequent words that can be decoded, such as "upward," and "got." These do not necessarily need deliberate instructional time because the students volition be able to read them using their knowledge of letters and sounds.

Regardless of the source, sight words can exist skilful using flash cards or give-and-take lists, making sure to review those that take been previously taught to solidify deep learning. Gradual introduction of new words into the card piles or lists should include introduction such as pointing out features that may help learning and memorization (e.g., "where" and "there" both have a tall letter "h" which can be thought of as an pointer or road sign pointing to where or there). Sets of words that share patterns can be taught together (e.one thousand., "would," "could," and "should"). Games such as Go Fish, Bingo, or Concentration featuring cards with these words can build repetition and exposure, and using peer-based learning, students tin can do speed drills with one some other and record scores.

Any action requiring the students to spell the words aloud is besides helpful. I invented an activity that I call "Can You Match It?" in which peers work together to practice a handful of sight words. An envelope or flap is taped across the top of a small dry out erase lath. One pupil chooses a menu, tells the partner what the word is, and and so places the card inside the envelope or flap so that information technology is not visible. The student with the dry out erase lath writes the word on the department of board that is not covered by the envelope, and so opens the envelope to run across if their spelling matches the discussion on the carte. The ultimate goal in all of these activities is to provide a lot of repetition and practice so that highly frequent, irregularly spelled sight words become words students tin can recognize with but a glance.

Discussion Recognition Summary

As seen in the above section, in gild for students to achieve automatic and effortless word recognition, three important underlying elements—phonological awareness, letter-sound correspondences for decoding, and sight recognition of irregularly spelled familiar words—must exist taught to the bespeak that they as well are automatic. Word recognition, the act of seeing a word and recognizing its pronunciation without conscious attempt, is ane of the ii critical components in the Simple View of Reading that must be accomplished to enable successful reading comprehension. The other component is language comprehension, which will be discussed in Affiliate 4. Both interact to grade the skilled process that is reading comprehension. Considering they are so crucial to reading, reading comprehension is likened to a 2-lock box, with both "key" components needed to open it (Davis, 2006).

The two essential components in the Simple View of Reading, automated give-and-take recognition and strategic language comprehension, contribute to the ultimate goal of pedagogy reading: skilled reading comprehension. According to Garnett (2011), fluent execution of the underlying elements as discussed in this chapter involves "education…accompanied past supported and properly framed interactive exercise" (p. 311). When give-and-take recognition becomes effortless and automatic, conscious endeavour is no longer needed to read the words, and instead information technology can exist devoted to comprehension of the text. Accuracy and effortlessness, or fluency, in reading words serves to articulate the way for successful reading comprehension.

It is easy to see how success in the iii elements that lead to automated word recognition are prerequisite to reading comprehension. Learning to decode and to automatically read irregularly spelled sight words tin can prevent the evolution of reading issues. Students who are successful in developing effortless give-and-take recognition have an easier time reading, and this serves equally a motivator to young readers, who and then go along to read a lot. Students who struggle with word recognition find reading laborious, and this serves as a bulwark to immature readers, who so may be offered fewer opportunities to read connected text or avert reading every bit much equally possible because it is difficult. Stanovich (1986) calls this disparity the "Matthew Furnishings" of reading, where the rich get richer—good readers read more than and become even better readers and poor readers lose out. Stanovich (1986) also points out an astonishing quote from Nagy and Anderson (1984, p. 328): "the least motivated children in the middle grades might read 100,000 words a year while the average children at this level might read 1,000,000. The figure for the voracious center grade reader might be ten,000,000 or even as loftier every bit 50,000,000." Imagine the differences in word and world noesis that result from reading 100,000 words a year versus millions! Equally teachers, it is worthwhile to go along these numbers in mind to remind u.s. of the importance of employing evidence-based instructional practices to ensure that all students learn phoneme awareness, decoding, and sight word recognition—the elements necessary for learning how to succeed in word recognition.

Summary

In order for students to embrace text while reading, it is vital that they exist able to read the words on the folio. Teachers who are aware of the importance of the essential, primal elements which lead to successful word recognition—phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition of irregular words—are apt to make sure to teach their students each of these then that their word reading becomes automatic, accurate, and effortless. Today'due south teachers are fortunate to have available to them a well-established banking company of research and instructional activities that they can access in lodge to facilitate give-and-take recognition in their classrooms.

The Uncomplicated View of Reading's 2 essential components, automatic word recognition and strategic language comprehension, combine to allow for skilled reading comprehension. Students who tin both recognize the words on the page and empathise the language of the words and sentences are much more likely to relish the resulting advantage of comprehending the meaning of the texts that they read.

Questions and Activities

- Listing the ii main components of the unproblematic view of reading, and explicate their importance in developing reading comprehension.

- Explain the underlying elements of word recognition. How does each contribute to successful reading comprehension?

- Hash out instructional activities that are helpful for pedagogy phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition of irregularly spelled, highly frequent words.

- View the following video showing a educatee named Nathan who has difficulty with word recognition: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lpx7yoBUnKk (Rsogren, 2008). Which of the underlying elements of word recognition (e.chiliad., phonological sensation, letter-sound correspondences, decoding) do you lot believe may be at the root of this student's difficulties? How might y'all develop a new instructional plan to address these difficulties?

References

Adams, Thousand. J., Foorman, B. R., Lundberg, I., & Beeler, T. (1998). The elusive phoneme: Why phonemic awareness is and then of import and how to help children develop information technology. American Educator, 22, 18-29. Retrieved from http://literacyconnects.org/img/2013/03/the-elusive-phoneme.pdf

Beck, I. 50., & Beck, M. East. (2013). Making sense of phonics: The hows and whys (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Printing.

Beck, I. 50., & Juel, C. (1995). The role of decoding in learning to read. American Educator, 19, 8-25. Retrieved from http://world wide web.scholastic.com/Dodea/Module_2/resource/dodea_m2_pa_roledecod.pdf

Blachman, B. A., Brawl, Due east. W., Blackness, R., & Tangel, D. M. (2000). Road to the code: A phonological awareness plan for immature children. Baltimore, Physician: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Blachman, B. A., & Murray, K. Southward. (2012). Teaching tutorial: Decoding teaching. Charlottesville, VA: Sectionalization for Learning Disabilities. Retrieved from http://teachingld.org/tutorials

Blachman, B. A., & Tangel, D. G. (2008). Road to reading: A program for preventing and remediating reading difficulties. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing.

Boyer, Northward., & Ehri, L. (2011). Contribution of phonemic segmentation instruction with letters and articulation pictures to discussion reading and spelling in beginners. Scientific Studies of Reading, xv, 440-470. doi:10.1080/10888438.2010.520778

Bradley, L., & Bryant, P. E. (1983). Categorizing sounds and learning to read: A causal connection. Nature, 303, 419-421. doi:10.1038/301419a0

Brady, S. (2011). Efficacy of phonics teaching for reading outcomes: Indicators from post-NRP research. In S. A. Brady, D. Braze, & C. A. Fowler (Eds.), Explaining individual differences in reading: Theory and prove (pp. 69–96). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Byrne, J. P. (2012). Encyclopedia of the Black Expiry. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Davis, Chiliad. (2006). Reading ins truction: The two keys. Charlottesville, VA: Cadre Knowledge Foundation.

Dehaene, Due south. (2009). Reading in the brain. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Elkonin, D. B. (1963). The psychology of mastering the elements of reading. In B. Simon & J. Simon (Eds.), Educational psychology in the U.S.S.R. (pp. 165-179). London, England: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Fry, Eastward., Kress, J., & Fountoukidis, D. (2000). The reading teacher's book of lists (4th ed.). Paramus, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Garnett, Thou. (2011). Fluency in learning to read: Conceptions, misconceptions, learning disabilities, and instructional moves. In J. R. Birsh (Ed.), Multisensory educational activity of basic language skills (p. 293-320). Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Goodman, Thou. (1967). Reading: A psycholinguistic guessing game. Journal of the Reading Specialist, 6, 126-135. doi:ten.1080/19388076709556976

Gough, P. B., & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7, half-dozen-ten. doi:10.1177/074193258600700104

Gough, P. B., & Walsh, One thousand. (1991). Chinese, Phoenicians, and the orthographic cipher of English. In S. Brady & D. Shankweiler (Eds.), Phonological processes in literacy (pp. 199-209). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

International Dyslexia Association. (2015). Definition of dyslexia . Retrieved from http://eida.org/definition-of-dyslexia/

International Reading Association. (1998). Phonemic awareness and the teaching of reading: A position statement from the board of directors of the In ternational R eading A ssociation . Retrieved from http://www.reading.org/Libraries/position-statements-and-resolutions/ps1025_phonemic.pdf

Nagy, Due west., & Anderson, R. C. (1984). How many words are there in printed school English? Reading Research Quarterly, 19, 304-330. doi:x.2307/747823

National Institute of Kid Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read: An evidence-based cess of the scientific enquiry literature on reading and its implications for reading educational activity: Reports of the subgroups . (NIH Publication No. 00-4754). Washington, DC: U.South. Regime Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/nrp/documents/report.pdf

Rayner, M., Foorman, B. R., Perfetti, C. A., Pesetsky, D., & Seidenberg, M. South. (2001). How psychological science informs the education of reading. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, two, 31-74.

Scarborough, H. South. (2002). Connecting early linguistic communication and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and do. In Due south. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (pp. 97-110). New York, NY: Guilford Printing.

Snowfall, C. E. (Chair). (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward an R & D program in reading comprehension. Santa Monica, CA: Rand. Retrieved from http://www.prgs.edu/content/dam/rand/pubs/monograph_reports/2005/MR1465.pdf

Snow, C. Eastward., Burns, M. Southward., & Griffin, P. (Eds.). (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Rsogren, N. (2008, June thirteen). Misunderstood minds chapter ii [Video file]. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?5=lpx7yoBUnKk

Stanovich, K. Eastward. (1986). Matthew furnishings in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Inquiry Quarterly, 21, 360–407. doi:10.1598/RRQ.21.4.1

Tunmer, W. Eastward., & Chapman, J. Westward. (2002). The relation of start readers' reported word identification strategies to reading accomplishment, reading-related skills, and bookish self-perceptions. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 15, 341-358. doi:x.1023/A:1015219229515

Worsley, L. (2011). If walls could talk: An intimate history of the home. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Endnotes

1: For detailed information on scientifically-based research in education, run into Chapter 2 by Munger in this volume. Return

Source: https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/steps-to-success/chapter/3-word-recognition-skills-one-of-two-essential-components-of-reading-comprehension/

0 Response to "Moving From the Old to the New: Research on Reading Comprehension Instruction"

Post a Comment